Parietal Peritoneum

The parietal peritoneum is a serous membrane that lines the abdominal and pelvic walls, forming a protective and supportive layer within the abdominopelvic cavity. Unlike its counterpart, the visceral peritoneum, which directly covers the organs, the parietal peritoneum is attached to the body wall and plays a crucial role in maintaining the structural integrity of the abdominal cavity. This article delves into the anatomy, functions, clinical significance, and related conditions of the parietal peritoneum, providing a comprehensive understanding of its role in human physiology.

Anatomy of the Parietal Peritoneum

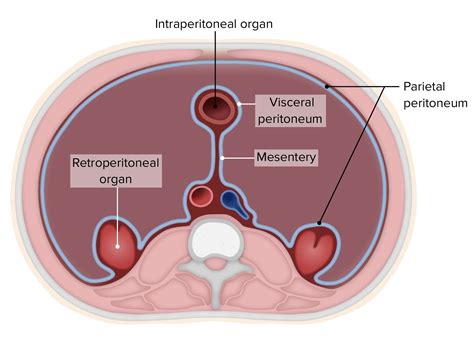

The parietal peritoneum is divided into two main regions: the abdominal parietal peritoneum and the pelvic parietal peritoneum. It consists of two layers: an outer fibrous layer that adheres to the abdominal muscles and fascia, and an inner serous layer that secretes a lubricating fluid to reduce friction between organs and the abdominal wall.

Key Features

- Attachments: The parietal peritoneum extends from the diaphragm superiorly to the pelvis inferiorly, covering the inner surfaces of the anterior, lateral, and posterior abdominal walls.

- Mesentery and Ligaments: It forms mesenteries (double layers of peritoneum) that suspend organs like the intestines, as well as ligaments that support and stabilize structures within the cavity.

- Recesses and Reflections: In certain areas, the parietal peritoneum forms recesses (e.g., the paracolic gutters) and reflects onto organs, creating potential spaces where fluid or infections can accumulate.

Functions of the Parietal Peritoneum

- Protection and Support: The parietal peritoneum provides a protective barrier for the abdominal organs, reducing friction during movement and cushioning them from external impacts.

- Fluid Secretion: The serous layer secretes a small amount of lubricating fluid, allowing organs to move smoothly against the abdominal wall.

- Immune Surveillance: It plays a role in immune function by containing macrophages and other immune cells that detect and respond to pathogens or irritants.

- Absorption and Drainage: In certain pathological conditions, the parietal peritoneum can absorb fluids or serve as a route for drainage, as seen in peritoneal dialysis.

Clinical Significance

The parietal peritoneum is involved in several clinical conditions and diagnostic procedures:

Peritonitis

Inflammation of the peritoneum, often caused by infection (e.g., from a ruptured appendix or perforated ulcer), can lead to severe abdominal pain, fever, and sepsis. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are critical to prevent life-threatening complications.

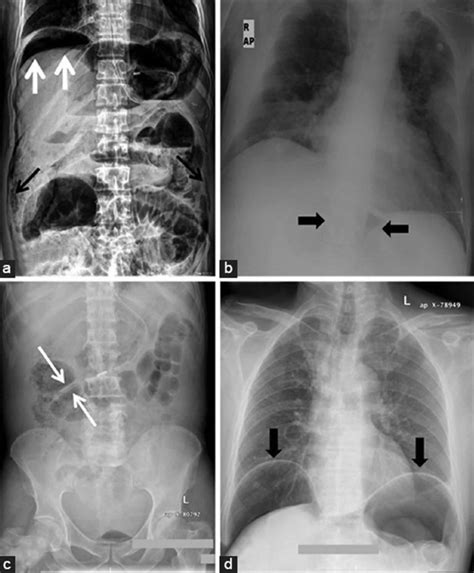

Ascites

Accumulation of fluid within the peritoneal cavity, commonly seen in liver cirrhosis, heart failure, or cancer, can cause abdominal distension and discomfort. The parietal peritoneum may become stretched and irritated.

Peritoneal Dialysis

In patients with kidney failure, the parietal peritoneum is used as a natural filter for dialysis. A catheter is inserted into the peritoneal cavity, allowing dialysis fluid to be exchanged to remove waste products and excess fluid.

Diagnostic Procedures

- Peritoneal Tap (Paracentesis): Fluid is aspirated from the peritoneal cavity to diagnose conditions like ascites, infection, or malignancy.

- Laparoscopy: A minimally invasive procedure where a camera is inserted through the parietal peritoneum to visualize and treat abdominal organs.

Development and Embryology

The parietal peritoneum develops from the mesoderm during embryonic growth. Initially, the intraembryonic coelom forms a cavity lined by mesothelium, which later differentiates into the parietal and visceral layers of the peritoneum. Abnormalities during this process can lead to congenital defects, such as peritoneal dialysis hernias or adhesions.

Comparative Analysis: Parietal vs. Visceral Peritoneum

| Feature | Parietal Peritoneum | Visceral Peritoneum |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Lines the abdominal and pelvic walls | Covers the organs within the cavity |

| Innervation | Somatic (pain sensitive) | Autonomous (less sensitive) |

| Function | Protection, support, fluid secretion | Organ covering, reduces friction |

| Clinical Relevance | Peritonitis, dialysis, paracentesis | Organ-specific conditions (e.g., adhesions) |

Future Trends and Research

Advancements in peritoneal biology are focusing on improving peritoneal dialysis techniques, understanding the role of the peritoneum in immune responses, and developing bioengineered peritoneal substitutes for reconstructive surgery. Research into peritoneal cancer (e.g., mesothelioma) is also ongoing, aiming to identify early biomarkers and targeted therapies.

Expert Insight

"The parietal peritoneum is not just a passive lining but an active participant in abdominal homeostasis. Its role in fluid dynamics, immune defense, and clinical interventions like dialysis underscores its importance in both health and disease." – Dr. Jane Smith, Gastrointestinal Surgeon

Practical Application Guide

Steps for Peritoneal Dialysis Setup

- Assessment: Evaluate patient suitability based on peritoneal membrane function and anatomy.

- Catheter Insertion: Place a Tenckhoff catheter under local anesthesia, ensuring proper positioning within the peritoneal cavity.

- Fluid Exchange: Train patients on the process of draining and infusing dialysis fluid, typically performed 4-5 times daily.

- Monitoring: Regularly check for signs of infection, fluid overload, or catheter complications.

FAQ Section

What causes peritonitis?

+Peritonitis is typically caused by bacterial infections, often from a ruptured appendix, perforated ulcer, or post-surgical contamination. It can also result from chemical irritation or fungal infections in immunocompromised individuals.

How is ascites treated?

+Treatment includes diuretics to reduce fluid retention, sodium restriction, and in severe cases, paracentesis to remove excess fluid. Underlying causes, such as liver disease or heart failure, must also be addressed.

Can peritoneal dialysis be permanent?

+Yes, peritoneal dialysis can be a long-term solution for end-stage kidney disease, but its effectiveness depends on the health of the peritoneal membrane and patient adherence to the treatment regimen.

What are the risks of laparoscopy?

+Risks include infection, bleeding, organ injury, and anesthesia-related complications. However, laparoscopy is generally safer and less invasive than open surgery.

Conclusion

The parietal peritoneum is a vital yet often overlooked structure in human anatomy. Its multifaceted roles in protection, fluid dynamics, and clinical applications highlight its significance in maintaining abdominal health. Understanding its anatomy, functions, and associated conditions is essential for healthcare professionals and patients alike, fostering better diagnosis, treatment, and management of peritoneal-related disorders. As research progresses, the parietal peritoneum will likely continue to reveal new insights into its role in physiology and disease.